Adventures and Relationships Coalesce in the Black Canyon

A cocky moment of overconfidence and impatience resulted in a broken ankle on the side of a 2,000-foot cliff in the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, about two weeks ago, the evening of Sept. 25.

I must admit, it is probably for the better. I can learn from this ... and catch up on things I've been neglecting –like writing, and my marriage, too, if I'm going to be perfectly honest about it.

Photo by Ryan Franz

“It’s times like these that challenge any relationship. Both people are treading water so vigorously, you forget the significance of your partner in the midst of the yawining ocean, and suddenly you’ve drifted apart.”

Mandi and I were married on the north rim overlook of the Black Canyon last June. The celebration marked not just our six years together, but a completion of a particularly difficult year leading up to it. My regular readers are familiar with the timeline: She was in the final semesters of grad school while working full time as a teacher, taking care of me through open heart surgery and the months of recovery that followed. We were planning our wedding (never an easy task). Our apartment flooded in January and took two months to fix. But it all came together – Mandi graduated with style, even though she was two months behind in the program at one point – and even the weather came together on our wedding day. We were in the clear. Finally. We played in the mountains all summer without too many concerns hanging over us. I climbed and climbed and climbed. I'm lucky to have an understanding wife who supports my goals as I support hers. But then life started happening again. Suddenly my employment at a small store was unstable because the owner suffered a medical emergency. The usual stressors of adult life piled on top of that, with both of us scrambling just to make sure the dog got walked every morning. We came home tired, did laundry, made dinner, washed dishes, zoned out for 30 minutes of NetFlix with a drink in hand, and did it all over again after another restless night of sleep. It's times like these that challenge any relationship. Both people are treading water so vigorously, you forget the significance of your partner in the midst of the yawining ocean, and suddenly you've drifted apart. It's a human condition.

Fall weather is also the moment of do-or-die for climbing glory in these parts. Climbers spend all year preparing for September-November. The clock is winding down, muscles are at their biggest, and so are the egos. It's time to grab your wildest dreams by the leg and see if you can hold on. I'm lucky Mandi understands. This year, I've been particularly obsessed, trying to make up for lost time after my heart surgery.

Jack romps up pitch five with a long way still to go up South Chasm View Wall, looming above.

"Astro Dog" was supposed to be little more than an introduction to the south rim of the Black. I'd never climbed the wall before, and the 1,800-foot route was a prelude to the bigger and harder routes my partner, Jack Cody, and I really wanted to do. What an introduction it was. Now my season is over, having ended once again in a hospital bed, this time from ankle surgery.

The fateful day

The 'Dog is a classic test piece from 1986 that's been on my ticklist for years, especially since Jack and I got rained out on our first opportunity last year. Getting to the bottom of the route entails 11 double-rope rappels from the rim, which eats up a lot of time. We started the descent just before sunrise and simul-rapped most of the rappels; we didn't reach the bottom until 8 a.m. With the days being shorter, we knew we would most likely finish the route by headlamp, so we were prepared. We banged out all the pitches up to the tenth, crux pitch. We averaged slightly less than an hour per pitch if you subtract the long rest we enjoyed at the Two Boulder Bivy Ledge (what a place!). In short, we were stomping through the route, and I was eager to stomp the much-hyped crux corner pitch: a steep, slippery dihedral with a thin crack for protection.

Looking down at Jack on Two Boulder Bivy Ledge from the top of pitch seven.

There's no debate that climbing is a selfish sport. It is. Such activities shape us, though. I discover what I'm made of. What partnerships are made of.

Jack took a while to finish pitch nine, leading up to the crux. A near-full moon dotted the empty sky as the sun set with a final flash of gold ribbon along the north rim, directly across from where I sat on a sloping ledge. All day long I'd been admiring the dramatic position of the north rim overlook where Mandi and I were married. It was a natural altar that plunged straight to the river from where the guardrail had restrained us from the thin air of oblivion. I remember the way the breeze tousled our hair that morning; the peaceful whispers from the abyss at our backs; the joyful murmurs of friends before us; and her smiling eyes, saying, "I do! I do! I do!" a thousand times before we said it. It all felt so far away from where I hung on the shadowed stone of Astro Dog.

A Black Moon Rises

Before Jack picked me up for the trip, Mandi suggested I leave my wedding band at home. It's never wise to climb with a ring on a finger, but I usually wear it on a leather necklace when I'm climbing. A 14-pitch route in the Black is not just another climb, though. I worried that with all the gear hanging off me, and with all the desperate, vertical bushwhacking I would surely do, my ring might not be safe even on a necklace. So I compromised by taking the ring with me and leaving it in the tent, which was about as far away as the north rim and all its memories from last June.

The sun set. The moon rose, and I thought of Mandi. Where might she be right then? Was she worrying about me? I doubted it. I like that about her. She knows how these adventures go. Besides, in more than 20 years of climbing, despite some wild, head-first falls, I'd never been hurt.

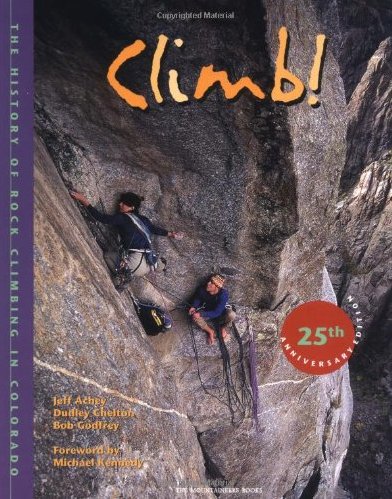

Shit. What is taking Jack so long? I thought. I was ready to finish in the dark, but I'd been hoping to see the crux pitch in daylight. "It's all yours!" Jack had said in the truck, laughing. "I do not want to lead that again," he said after enduring an 18-hour mini-epic with a less qualified partner on the route a couple weeks before. I was happy to have the crux pitch. Ever since I saw it on the cover of Jeff Achey's book, "Climb!" I knew I wanted to lead it. It looked blank and menacing in the photo. And now I'll be onsighting it by headlamp, I thought, clipping my torch to my helmet as Jack pulled up the rest of the rope from above, out of sight.

Jack follows pitch eight (5.11a), an awkward finger crack in the back of a flare.

I could see why Jack took longer than anticipated to lead pitch nine. It traversed around on gritty face holds between the only small seams that offered protection. At one point, I followed the rope up and under a detatched, van-size block that overhung the void. I was scared to bump it with my helmet, much less pull on it, but Jack had placed gear under it for lack of anything else. Above the block, a thin traverse led across the face to an incipient finger crack and Jack's belay.

“I kept thinking of a photo of a guy with a broken back who fell somewhere on the route and had to spend the night until rescuers got to him. I thought (and hoped) we’d already passed that spot, but I would find out later we were just getting to it.”

"Dude, for how scary it is, I can't believe there isn't a word about this pitch in any of the topos or descriptions!" he said. It was spooky. It didn't sit well with the ominous feeling I'd kept stuffed down the whole trip. Any foray into the Black has an ominous tinge to it, though. I kept thinking of a photo of a guy with a broken back who fell somewhere on the route and had to spend the night until rescuers got to him. I thought (and hoped) we'd already passed that spot, but I would find out later we were just getting to it.

The crux was 30 feet of glassy rock in a corner that slanted oppressively to the left. I shined my torch over the looming dihedral, noting key features. Distances are much harder to judge by headlamp, though. I wouldn't really know anything until I got up in it. With a full rack of jangling metal, a backpack and a tagline attached to me, I stepped onto the small triangular ledge that would come to define so much about that night; the same bone-breaking ledge that has claimed other victims.

I could have spent more time looking around. It was already dark, so what would a few more minutes have been? Patience saves lives – I intend to remember that. If I'd taken more time, maybe I would have seen the hand holds behind me, or placed better protection than the marginal, tiny brass nut above my head. As it was, eager to get on with it, I pulled into the corner. My fingers crimped, white-knuckled on a single edge. My feet smeared against the face.

Back off! This isn't the way, a voice whispered in my head. Back off now while you still can.

Shut up, I retorted. Maybe it's not the way, but I got this.

I was inches away from a small opening in the crack when I fell. The brass nut at my waist popped out instantly, and I dropped onto Jack. My right foot clipped the ledge as I sailed by.

"Aaaahhh!" There was instant pain. I knew I was hurt, and hoped it was just a bad sprain. I convinced myself I could still climb on it as long as I didn't have to weight it in certain positions.

“Sometimes it’s better to make a small compromise that greatly improves safety.”

I rubbed my ankle for a several minutes and contemplated my destiny. The long rest allowed me to see what I missed before, so I pulled back on for another go. This time I set better protection by standing in a sling to reach a good placement with a tiny cam – something I was unwilling to do before, because it would mar any claim for a clean onsight. Sometimes it's better to make a small compromise that greatly improves safety. I had certainly been reminded of that.

A broken man

The cover of the book, "Climb! The History of Rock Climbing in Colorado," features Astro Dog's crux pitch.

I sent the crux. It was a miracle, and I felt damn proud, stemming up the corner to victory. I was making the final moves onto easier rock at the top of the dihedral when my right foot gave out for good. I'd stepped through to stand on the slab and found I couldn't weight the foot. I tried three times, but the foot was like a noodle that wasn't even attached to me. There was a disturbing sensation of things shifting around under the skin, and I knew it was hopeless to keep climbing above my gear. I downclimbed a few moves and dropped onto my highest cam – a scary fall for Jack to catch as it was. My back slammed into the corner, but I hardly noticed. Blood gushed from a flap of skin on my finger, which was numb from the trauma. My foot throbbed. It took a while for my breathing to calm down.

Jack and I traded rope ends so he could yard up to my high point and finish the pitch. I sat in the dark, belaying with my headlamp off to conserve batteries.

How do I make this right? I thought. I felt a heavy responsibility for the situation. My decisions had put us there. Now Jack had to lead the rest of the pitches and help me claw my way out of this hole. Damn the pain, you better haul every ounce of your weight you can muster, because you owe your partner that much effort, I thought. If I was going to be a cock-headed ninny going for the glory, I better be an equally tough motherf***er when it came to getting my crippled ass out of there, or else I was just a weak sack of meat who shouldn't have hung it out there so far in the first place.

I grunted. I wailed in pain. I pulled on slings and climbed with my knee jammed into the rock when I had to. The sounds I made would have given me chills if I'd been a distant bystander, listening to the echoes of cries and jangling metal in the moonlight. I was slow, but I was able to follow Jack's rope to the top.

Every time I sat in darkness at a belay, I contemplated the space and landscape the enveloped me. It was a beautiful night, and we were still laughing, almost happy to be exactly where we were.

Jack's positive attitude never faltered. It confirmed my decision in him as a partner. By the time we reached the top at 1 a.m., I already had plans to come back with him, though I couldn't bring myself to say it then. We went back to camp and built a fire. We slugged whiskey under the stars.

"I still wouldn't call this an epic," Jack said.

"Nah, but it sure as hell was an adventure."

Can't Let Her Down

Back home with Mandi, I realize I'm still on a wall of sorts. Only it's with her. Because of my decision and my injury, I've had to miss work, and I've incurred more doctor bills. I can't walk the dog in the mornings, or grocery shop, or drive. She's having to pick up the slack, again, and it's my fault this time. The heart surgery wasn't my fault last year, but this one is on me. So I better keep pulling my weight as best I can, as much as it sucks. I owe her that. The adventure is not over.

I sit here, writing this, and can you believe I feel incredibly lucky? I do. I am lucky to have such good partners in life.

“In this case, I have a much deeper awareness as to how a tiny moment ripples through time, over many lives beyond my own.”

Immediately after the accident, I wondered if I had any business being up there on that climb. I felt like a fool. Then I realized I did everything right except for the one minute of hastiness. I picked my partner well, we were well prepared, and we got ourselves out of there. It didn't go as planned, but we weren't unreasonable in being there.

I will continue to climb. I know myself well enough to know that's not going to change. Mandi knows it, too. That probably means I'm a selfish bastard by some people's standards. But I think back to those moments under the moon and stars, among those rolling swells of silver cliffs, and what I felt there makes the journey completely worth it.

For one thing, I've learned, and intend to keep learning, in all things I do. In this case, I have a much deeper awareness as to how a tiny moment ripples through time, over many lives beyond my own.

We are connected. We affect one another, even in fleeting decisions that seem small and personal. Together we rise. Or fall.

I carry the weight of my loved ones with me wherever I go. To ignore or deny that would be irresponsible.

Epilogue

My ankle starting to swell the morning after

My talus bone was fractured, an injury commonly referred to as "snowboarder's ankle." I had surgery Oct. 6 to remove the small bone chips that were floating in the joint. In the big picture, it's a minor injury, and I'll probably be back to climbing in a couple months. Unlike my situation after heart surgery, at least I will be able to keep my upper body in shape while I recover.

Meanwhile, 36 hours after our adventure, Jack got a call notifying him that a slot had opened up for a weeklong AMGA (American Mountain Guides Association) exam in Red Rocks, Las Vegas. It's like a doctorate degree for climbing guides. He'd been waitlisted to take the test for more than a year. So he drove out on short notice about as soon as he could rub the Black grit from his eyes. He passed the rigorous tests, and immediately drove to Yosemite, where he climbed the Salathé Wall (35 pitches) on El Capitan in 25 hours. He'd never climbed El Cap before. When I climbed the Salathé 10 years ago, I spent four nights on the wall. My buddy is a bad ass!

Jack Cody, still smiling, hours after scraping our way out of the canyon by headlamp.